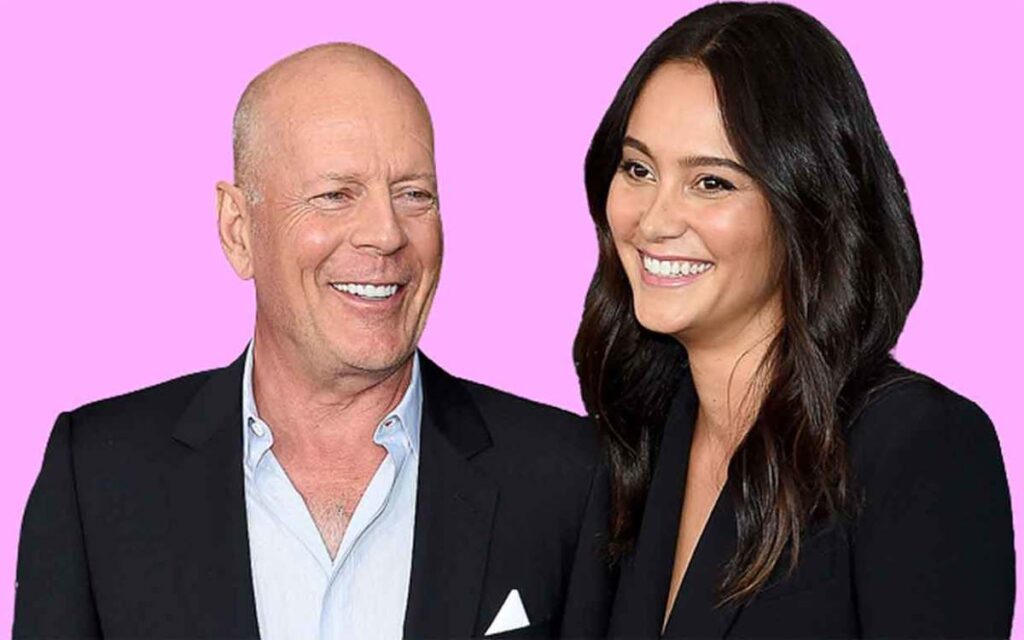

Bruce Willis has frontotemporal dementia

This Thursday, Bruce Willis’ family revealed that the 67-year-old star has been identified as having frontotemporal dementia (FTD).

The information was released about a year after it was revealed that Willis would retire from acting owing to a diagnosis of aphasia, a language condition that affects one’s capacity for speaking, reading, and writing.

According to a study conducted by scientists at Columbia University in New York City, one in ten people over 65 had dementia.

Definition of FTD

The term frontotemporal dementia (FTD) describes a group of ailments characterized by the degradation of brain nerves in the frontal and temporal regions of the brain, which are involved in behavior, personality, and language. According to Willis’ family, his initial diagnosis of aphasia may have been a sign of FTD.

FTD comes in a variety of forms. One mostly affects behavior and personality because it causes the degeneration of nerve cells necessary for judgment, behavior, and empathy. Another typically manifests in midlife and has an impact on language, speaking, and writing. Another form of FTD, known as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, particularly affects the motor nerves. There are conflicting estimates of the number of persons who have FTD, but the Alzheimer’s Association assumes that between 50,000 and 60,000 Americans suffer from the behavior and language symptoms of the disease.

Are FTD and Alzheimer’s disease the same thing?

While FTD also includes a slow loss of brain nerves, there are several significant differences between it and Alzheimer‘s. While Alzheimer’s patients are often diagnosed later in life, FTD patients are typically diagnosed in their 40s to 60s. While speech issues are more frequent in FTD, memory loss and disorientation are more frequent in Alzheimer’s.

Patients with FTD experience aberrant protein deposits of either tau or TDP-43, but not both of these proteins. Tau does accumulate in Alzheimer’s patients, but in a different form than in FTD. FTD is often more challenging to diagnose. Dr. Ryan Darby, director of the Frontotemporal Dementia Clinic at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, states that efforts are being made to create blood, spinal fluid, and PET scan markers to diagnose FTD, but these are still under development. At the moment, there are no reliable tests for FTD available, unlike those for Alzheimer’s.

Brain scans, which can offer some helpful suggestions but aren’t conclusive, and sometimes the patient’s full list of symptoms are used by doctors to make a diagnosis. Also, “we frequently undertake tests to rule out other types of dementia like Alzheimer’s dementia,” adds Dr. Nicole Purcell, a neurologist and senior director of clinical practice at the Alzheimer’s Association.

About one-third of FTD cases, according to the Alzheimer’s Association, are genetic. For the non-genetic instances, there are no established risk factors, making it challenging to spot potential FTD sufferers.

It’s essential to know which of the two proteins is improperly accumulating in order to create the best remedies. While TDP43 is involved in some language-related FTD cases, Darby notes that individuals with behavioral symptoms can have elevated levels of either protein, making it challenging to decide which protein should be the focus of treatment studies.

Exist treatments?

There is a lot of research being done to better understand FTD and its causes, but there are currently no cures for the neurodegenerative disease. Antidepressants and anti-anxiety drugs can lessen some of the agitation and tension that patients feel, but there are currently no treatments available to stop the progressive degeneration of neurons in the brain regions affected.

According to Dr. Claire Clelland, assistant professor of neurology at the University of California San Francisco, researchers are concentrating on the hereditary variations of the condition to understand more about how it functions and the best ways to interfere with potential remedies. She claims, “We believe that is the greatest and quickest road to clinical trials for innovative medicines.” We will gain a broader understanding of the condition in hereditary cases where the underlying cause is known due to a gene mutation, enabling us to assist more individuals.

In recent years, research into the disorder has increased, and medical professionals who care for FTD patients in academic settings have worked together to identify and track patients in order to share information and be ready to test promising new pharmacological therapies as soon as they are created. “During the past twenty years, our understanding of FTD has actually advanced substantially,” claims Darby. While the clinical syndrome was first diagnosed in the 1990s and the gene for the most prevalent hereditary type wasn’t found until 2011, a lot of our understanding has advanced since then. Many of us are optimistic that the recent wave of invention will lead to new treatments.

Clelland concurs with that hope. These issues are developing into solvable ones, she claims. “Cells from patients have already been essentially healed in my lab. All that remains is to determine how to administer the therapy to patients.

She praises Willis and his family for sharing their experience in order to spread awareness of the illness and possibly spur additional study.

According to Willis’ family, Bruce “always believed in utilizing his voice in the world to help others, and to raise awareness about vital causes both publicly and personally.” “We know in our hearts that if he could, he would want to respond by bringing awareness to those who are also suffering from this crippling condition and how it affects so many people and their families on a global scale… We hope that any media coverage may be directed toward bringing awareness to this disease, which requires a great deal more study and awareness as Bruce’s health worsens.